How tweed became a symbol of Scottish culture

In Scotland’s hills and islands, textile traditions touch on sustainability and local pride while making a mark in high fashion.

Bending over her 80-year-old, cast iron loom, 27-year-old weaver Miriam Hamilton begins the clickety-clackety process of turning wool yarn into tweed. She’s carrying on a centuries-long tradition in her loch-side workshop on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, a chain of islands off the west coast of Scotland. Still, the ombre, nubby-textured fabric Hamilton makes will be turned into brightly colored men’s vests or used to cover chic lampshades, not old-school hunting jackets or Sherlock Holmes caps.

“I want my tweed to mimic the patterns in nature,” says Hamilton, who works out of The Weaving Shed in the town of Crossbost. She learned to weave from a 90-year-old crofter (tenant farmer and craftsman) in 2018, but she infuses her fabrics with her own energy and palettes. “It could be the colors of the loch or the graduation from deep plum to mulberry to lilac in a thistle’s flower,” she says. “It’s a reflection of the drama in this environment.”

Like many traditional practices born in the countryside of Scotland, tweed draws inspiration from the surrounding landscape and materials from its sheep-filled fields. The hard-wearing, all-weather textile hearkens to an older, simpler way of life, its history touching on both the doings of British royals and local farm life.

But the present—and future of tweed—suggests a happy marriage between these remote crafting communities and big city fashion designers, between age-old fabrications and cutting-edge technology. Here’s where this Scottish textile came from, and where it’s going next.

The birth of tweed

No one town or mill owns the history of tweed. Woolen fabrics have been part of daily life in Scotland for centuries, worn by farmers, game wardens, and athletes. Like the country’s other enduring Celtic textile traditions—clan tartans and fuzzy, zigzag pattern Fair Isle sweaters—tweed ties into geography, national pride, and the need to bundle up in the often chilly weather.

“It’s firmly rooted in crawling over hills in the coldest, wettest rain imaginable,” says Stephen Rendle, managing director of Lovat Mill, which has been producing tweed in the bucolic Scottish Borderlands river town of Hawick since 1882.

Simply put, tweed is a subtly patterned fabric made from dyed, spun, and woven wool from hardy local sheep. It’s been created in Scotland since the early 18th century, coming from outsized looms that spit out yardage from yarns originally dyed with the native lichen and wildflowers.

Don’t confuse chunky, speckled tweed with tartan, its flashier cousin. Tartans are also woven, but they flaunt bolder cross-checkered patterns in two or more colors, and can be made of wool, silk, or a blend. Tweed goes shooting, hunting, or chasing after livestock; tartan is the ceremonial stuff of kilts and legendary Highland chieftains.

Tweed got its name by accident in 1826 in Hawick, when a merchant’s label on a shipment of wool tweel (the Scottish term for twill) bound for a London milliner was misread and confused with the moniker of the nearby River Tweed. Soon after, boosted by fresh techniques that made dyes brighter, and new train routes between Scotland and London, Hawick and neighboring Galashiels became textile boomtowns with more than 20 mills producing tweeds.

Then and now, tweed is usually made of dense fleece of the white-faced Cheviot sheep, which graze in the surrounding Cheviot Hills. Durable, warm, and waterproof, the thick woolen material became a farmer favorite, hallmarked by small, often-subtle crisscross patterns known as “shepherd’s check” or “houndstooth,” the latter named for its jagged, incisor-like appearance.

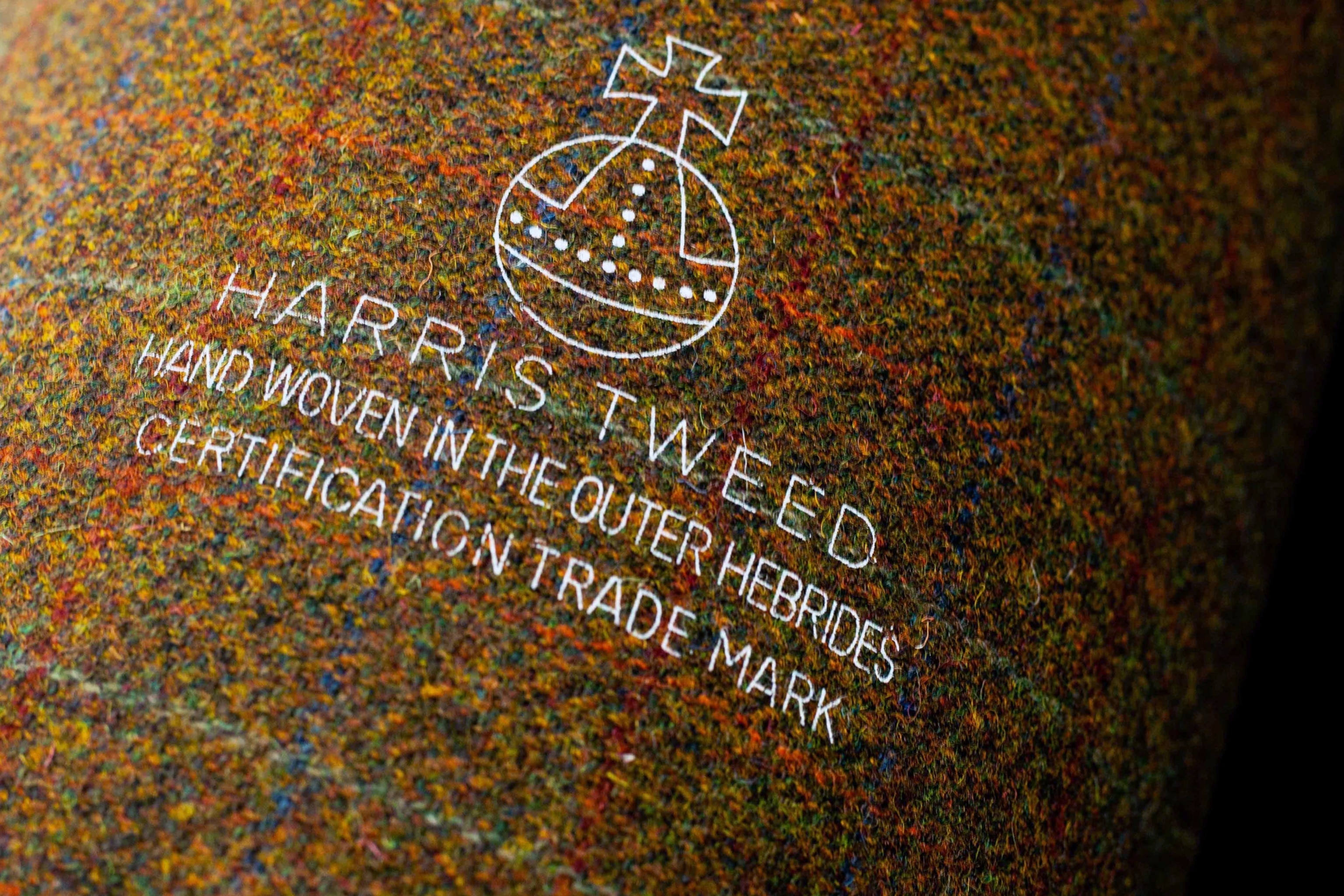

Though some tweed is produced in England, Ireland, and Germany, the majority still hails from Scotland. There are two main types: the colorful, tightly woven Harris Tweed of the Outer Hebrides and the more earthy-hued fabrics of the Scottish Borderlands and Highlands.

Harris Tweed powers small crafters

Harris Tweed has been created for hundreds of years beside the moor-framed bays of the Outer Hebrides. Called an clò-mòr in Gaelic, it’s characterized by rich waves of color and must be handwoven with a warp of either 700 or 1,400 individual threads. The coarse textile is still homemade in remote weaving sheds from pure virgin wool dyed and spun on the islands.

“Scotland, the Hebrides in particular, is almost a fantasy land of weavers,” says Mark Hogarth, creative director of Harris Tweed Hebrides, which produces about three-quarters of the world’s Harris Tweed. To safeguard the fabric and the island chain’s fragile economy, a watchdog group, Harris Tweed Authority, was set up in 1909 to represent the area’s 190 self-employed weavers and 9,000 different patterns.

The Scots are so protective of Harris Tweed that, in 1993, they spearheaded a successful act of parliament prohibiting mills outside of the Outer Hebrides from labeling other fabrics Harris Tweed.

“Harris Tweed runs in our veins,” says Lorna Macaulay, chief executive of the Harris Tweed Authority. “It’s made by socially isolated communities, and you can’t understate the cloth’s importance—economically, historically, and culturally—to island life.”

Visitors can see the fabric being made at the Harris Tweed Authority in Stornoway or at Hamilton’s Weaving Shed, where she also whips up vests, scarves, and bags. You can buy woolly Hebridean souvenirs at all these spots or from Borrisdale Tweed in Leverburgh, which offers caps, pillow covers, and bags.

Hardworking tweeds of the Highlands and Borderlands

Unlike the brighter swaths of the Outer Hebrides, tweeds from the Scottish Borderlands and Highlands come in mossy greens and muted, earthy browns, a sort of aristocratic camouflage recalling gamekeeper uniforms and pipe bands. All around, the soft waters of the rivers Tweed, Teviot, Jed, Ettrick, and Gala once washed the wool and powered the mills. Today, only a handful of mills remain.

In the Borderlands, tweed twists through the past and present. Hawick’s Borders Textile Towerhouse fills a 500-year-old stone building with a museum of clothing, equipment, and photos documenting two centuries of fabric making.

Nearby, Lovat Mill is the town’s last working mill, where cutting-edge, carbon-fiber rapier looms purr out tweeds that are increasingly lightweight, malleable, and sometimes, Teflon-infused for durability. At the mill’s factory shop, you can buy blankets and scarves made from the same materials used by Gucci, Chanel, and Thom Browne.

There’s a similar blend of heritage and fashion in the Highlands, where tweed acts as a foil to the more ceremonial tartans. Johnstons of Elgin in Moray has been operating on the banks of the Lossie River since 1797, but its dense tweed now gets turned into houndstooth bomber jackets and dashing fringed scarves that’d suit Parisian streets as much as Inverness hills. Guided tours of the mill show off its kaleidoscopic patterns and expert weavers.

“There are no real limits to the number of colors we use in contemporary designs,” says Johnstons’ creative director Alan Scott. “We may use between six to eight colors in a single mélange or 16 colors in a twist. There can be hundreds of colors in one tweed.”

Tweed in fashion

Tweed captures moments in time, shuttling in and out of style. One of its biggest boosters was Prince Albert, who bought Balmoral Castle in Aberdeenshire with Queen Victoria in 1853. Estate tweeds, fabrics woven specifically for the workers and residents of Highlands properties, were popular at the time. The prince helped to create a speckled granite and crimson heather pattern to represent the royal family’s country digs which is still used today.

(Queen Victoria’s jewels tell the story of her reign and her love for Prince Albert.)

It spurred a sturdy fabric craze among the swells back in 19th-century London. Savile Row’s strong tailoring turned the homey fabric into well-cut jackets and other suiting fit for high society. “Prince Albert was the original torchbearer of the tweed tradition,” says Kirsty Hassard, curator of exhibitions and fashion historian at Victoria & Albert Dundee, the Scottish outpost of the London design museum. Woolens became such a status symbol that Arthur Conan Doyle clad his fictional sleuth Sherlock Holmes in a tweed deerstalker hat in 1893.

The British royals still suit up in the fabric today. Queen Elizabeth II dons sensible woolies with wellies at Balmoral, and the younger generation supports the industry, too. “That thread runs through to the Duchess of Cambridge [Kate Middleton], who chooses designers that use tweed in innovative ways,” says Hassard. Princess Kate has been photographed in tweed miniskirts and mod dresses by British firms like Alexander McQueen and Catherine Walker.

(Learn how Beau Brummell revolutionized British menswear in the 19th century.)

Tweed goes global

By the 20th century, tweed became popular around the world, with its rich weaves and checks showing on pro golfers’ pants, Ivy League professors’ blazers, and haute couture. Paris designer Coco Chanel swooned for the fabric in the 1920s after borrowing her lover’s jacket. She began incorporating nubby Scottish (and later French) varieties into her suits and frocks. John F. Kennedy and Sean Connery sported Harris Tweed blazers in the 1950s and 1960s. Even Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay turned out in tweed to take on Mount Everest.

Scottish tweed is almost as popular in the United States as it is in the U.K. When the ivy or preppy look first sailed into fashion in the 1960s, an astonishing 70 percent of global Harris Tweed sales went to the east coast of the U.S. The fabric’s collegiate, New England-meets-Old England style still shows up at retailers including Todd Synder, Brooks Brothers, Boden, and Supreme, often in unexpected forms like baseball caps and crossbody bags.

In the U.K., younger designers embrace Scottish tweed, too, including Glasgow’s Charles Jeffrey, whose Loverboy label uses it and tartans in unexpected, unisex clubwear (scarf-draped trousers, Matrix-length trench coats) and Jamaican-Scottish designer Nicholas Daley, whose menswear meshes reggae motifs, African shapes, and tweed.

“Tweed is a fashion statement that speaks to tradition,” says Hassard. “But it also remains at the cutting-edge because of its practicality and eye-catching look. All the blues and golds of the Hebrides’ beaches and the greens and browns of the Highlands are reflected in its colors, and that sets tweed apart from every other fabric.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

Science

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

Travel

- How to plan an epic summer trip to a national parkHow to plan an epic summer trip to a national park

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads