Fossil-finding ants amass huge haul of ancient creatures

Paleontologists have just discovered 10 new species of ancient mammal thanks to the tiny mound-building insects.

Across the western United States, the industrious insects known as harvester ants are often cast as pests. These ants gather seeds and live in large sediment mounds, and they can deliver nasty stings to creatures they perceive as threats. A mound can last for decades and, to the chagrin of some property owners, the land up to 30 feet away is protectively picked clean of vegetation.

But as these ants construct their mounds, they do something remarkable: act as the world’s smallest fossil collectors.

The colonies clad their mounds with a half-inch-thick layer of small rocks about the size of beads, possibly to protect the structures from wind and water erosion. To find material for this cladding, the ants venture more than a hundred feet from the mound. In addition to bits of gravel, they gather up any tiny fossils and archaeological artifacts that they happen upon.

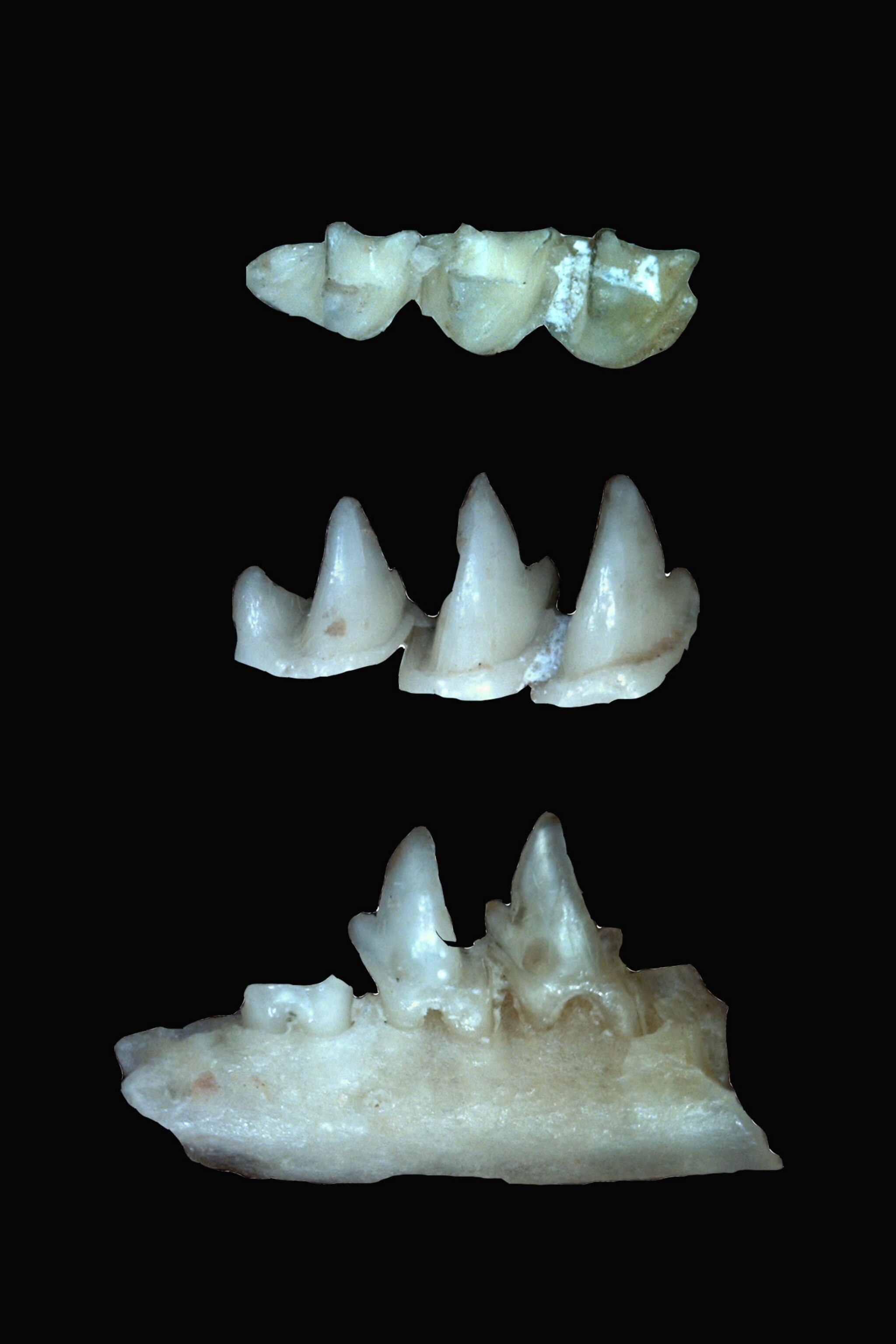

The scientific bounty these ants can accumulate is staggering. Examining 19 harvester ant mounds on one property in Nebraska, researchers recently found more than 6,000 microfossils—each no more than a few millimeters wide—from ancient mammals. The specimens include small teeth and jaw fragments that represent nine new species of rodents and a new species of insect-eating, shrew-like animal.

The fossil haul, described recently in the scientific journal Paludicola, also includes the teeth of primates, ancient cousins of rabbits, and an unidentified species of bat. Small though these teeth may be, their shapes provide a wealth of information—including where the teeth fall on the mammalian tree of life.

“It gives us this concentrated source of fossils that otherwise would take either a lot of our effort having to dig through rock … or just years and years of having to crawl around on our hands and knees, hoping to find something loose,” says study co-author Clint Boyd, a paleontologist at the North Dakota Geological Survey in Bismarck.

And thanks to the ants’ efforts, researchers can use these fossils to better understand what was going on in North America about 34 million years ago, an evolutionarily important period that marked the end of the Eocene epoch and the beginning of the Oligocene. During this time, the planet entered a prolonged cooling period, driving some species extinct and rearranging ecosystems across the ancient Earth.

“Harvester mounds are like archaeologists’ and paleontologists’ best friends,” says National Geographic Explorer Benjamin Schoville, an archaeologist at Australia’s University of Queensland who wasn’t involved with the study.

Tiny fossil hunters

Ants’ unwitting knack for fossil-hunting has been known to scientists for more than a century. In an 1896 publication on fossil sites in the western U.S., paleontologist John Bell Hatcher advised collectors to frequent local anthills, “as they will almost always yield a goodly number of mammal teeth.” Hatcher’s preferred method for nabbing teeth—sieving the sediment with a flour sifter—seems to have worked well. He boasted that he regularly found 200 to 300 individual teeth and jaw fragments on just one hill.

As well-documented as the ants’ behavior is, though, it’s taken on the flavor of folk knowledge—widely understood but not systematically studied. The few studies done so far, however, have shown that harvester ants can pick up some remarkable specimens.

In 2009 a team led by Schoville published the results of observations it made from 812 ant mounds in Nebraska. Of these, nearly a fifth had small flakes chipped off stones, perhaps debris left by Native Americans who sharpened stones into tools or projectile points. “Some debris from human occupation is only represented by those small artifacts,” he says.

The study also demonstrated just how far the ants will travel. In one experiment, Schoville’s team arranged beads in concentric rings around several mounds. The farthest of these rings lay 48 meters (157 feet) from the peaks. To Schoville’s surprise, ants at one of the mounds brought beads back from that far-flung distance—roughly equivalent to a human foraging seven miles from home.

Combing the plains

The new study, also done in Nebraska, came about from the dogged efforts of the Gulotta family, which owns the ranch where the study’s mounds sit.

Marco Gulotta, Sr., an avid amateur fossil collector, knew that harvester ant mounds could yield tiny teeth and bones. In concert with his sons Mel and Marco Jr., Gulotta gathered gallons’ worth of gravel from the mounds’ outermost layers, used a sieve to separate the material, and picked through the pebbles for ancient remains. Gulotta then began posting photographs of his finds on the Fossil Forum, an online community of paleo-enthusiasts.

Boyd and his colleague Deborah Anderson, a paleontologist at St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin, saw the posts and contacted Gulotta, persuading him to send Anderson some of the microfossils. From there the project snowballed, with Anderson, Boyd, and Bill Korth of the Rochester Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology in New York teaming up to review thousands of tiny remains.

Through it all, the researchers worked closely with the Gulotta family. In the fall of 2020 Boyd visited the ranch to catalog the ant mounds’ locations with GPS. The Gulottas donated the thousands of microfossils analyzed in the study to the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, where they will be available to future researchers.

“Sometimes some people see, you know, a bit of antagonism between academic paleontologists and landowners when it comes to fossils,” Boyd says. “But this is a good example of how we can all work together and accomplish important scientific research.”

The prehistoric Midwest

When these fossils originally formed—between 37 million and 32 million years ago—the Great Plains of what is now the central U.S. were warmer, wetter, and more forested, says Korth, the new study’s lead author. The fossils therefore capture a small slice of mammalian life in these muggy environs.

Many of the remains probably derive from predator’s scat, after the small animals were eaten and digested. Once buried, the teeth and bone fragments fossilized—and they are remarkably well-preserved.

Not only do these fossils, each just millimeters across, include 10 new species of small mammals, they also fill in the biology of known creatures, revealing never-before-seen types of teeth from several extinct rodents. “There were some species that were known from two or three specimens that we have thirty to forty specimens of now,” Korth says.

The harvester ants gather gravel pieces of a certain size, so only fossils of that size will make it to their mounds. “They’re not going to build a perfectly curated museum assembly,” Schoville says.

Even so, thanks to GPS coordinates and knowledge of the topography, Korth and Boyd’s team were able to determine the specific layers of rock that each ant mound sampled across. By tracking which types of fossils were found at each mound, the researchers could estimate when different species appeared and disappeared in the site’s rock layers. This information then let the team infer which rock layers in this part of Nebraska record the end of the Eocene and the start of the Oligocene epoch about 34 million years ago.

To the researchers’ delight, their ant-based estimate matches an estimate made 13 years earlier with a different method—meaning ant mounds may provide an independent way to refine the boundaries of geologic time. That’s all the more reason to look to harvester ants as humans’ partners in paleontology.

“You walk landscapes looking for fossils,” Schoville says. “You should also be looking for ant mounds along the way.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital