Face-mask recognition has arrived—for better or worse

New algorithms can police whether people are complying with public health guidance. The practice raises familiar questions about data privacy.

Public shaming over not wearing a face mask started almost as soon as the COVID-19 pandemic itself. In February, some provinces and municipalities in China made it mandatory to wear masks when in public. News reports soon followed of residents and police chastising the non-compliant, a trend that’s now seen globally.

When Akash Takyar heard those early stories trickle out of China, he was shocked at how things were being handled, and he wondered if his software company—LeewayHertz—could offer a more peaceful way. Takyar recognized how important it is to wear a mask to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. But rather than leave members of the public to monitor each other, he wanted to develop a computer program that could look at images and detect whether people are wearing masks.

His San Francisco-based company is one of many now pioneering mask recognition as a way to get people to comply for the public good. So far, masks have been confounding traditional facial recognition software—but these new machine learning tools could conceivably be used in private or public spaces to measure compliance and ostensibly take that out of the hands of individuals.

To date, 34 states and the District of Columbia have mask mandates for public spaces, both outdoors and indoors. But compliance can vary depending on a range of factors, from personal politics to an individual’s financial ability to purchase masks. For the most part, people who flout the mandates even if they can afford to follow them get away with that noncompliance. Only a few reports—from Nevada, Louisiana, and Indiana—show that law enforcement has stepped in to arrest people who were indoors in private businesses without a mask.

For businesses that have workers returning to indoor facilities, noncompliance could lead to others in the workplace getting infected. Ultimately, it could be a great loss for a business if there was an outbreak because someone was asymptomatic and failed to wear a mask, says Takyar.

But “face data is as precious as a fingerprint,” says Deborah Raji, a fellow at the AI Now Institute at New York University. And those who have had qualms about facial recognition wonder whether mask recognition software, as well intentioned as it may be, should have a place in today’s society.

How to scan a face mask

Today’s facial recognition software studies the features around the eye, nose, mouth, and ears to identify an individual whose picture is already supplied, either by the individual or in a criminal database. Wearing a mask obstructs this recognition—an issue that many systems have already encountered, and others have solved. For example, Apple’s FaceID, which uses facial recognition so users can unlock their iPhone, recently released a system update that can, in essence, detect when a person is wearing a mask. The update quickly recognizes a covered mouth and nose and prompts the user to enter their passcode instead of making them pull down their face covering.

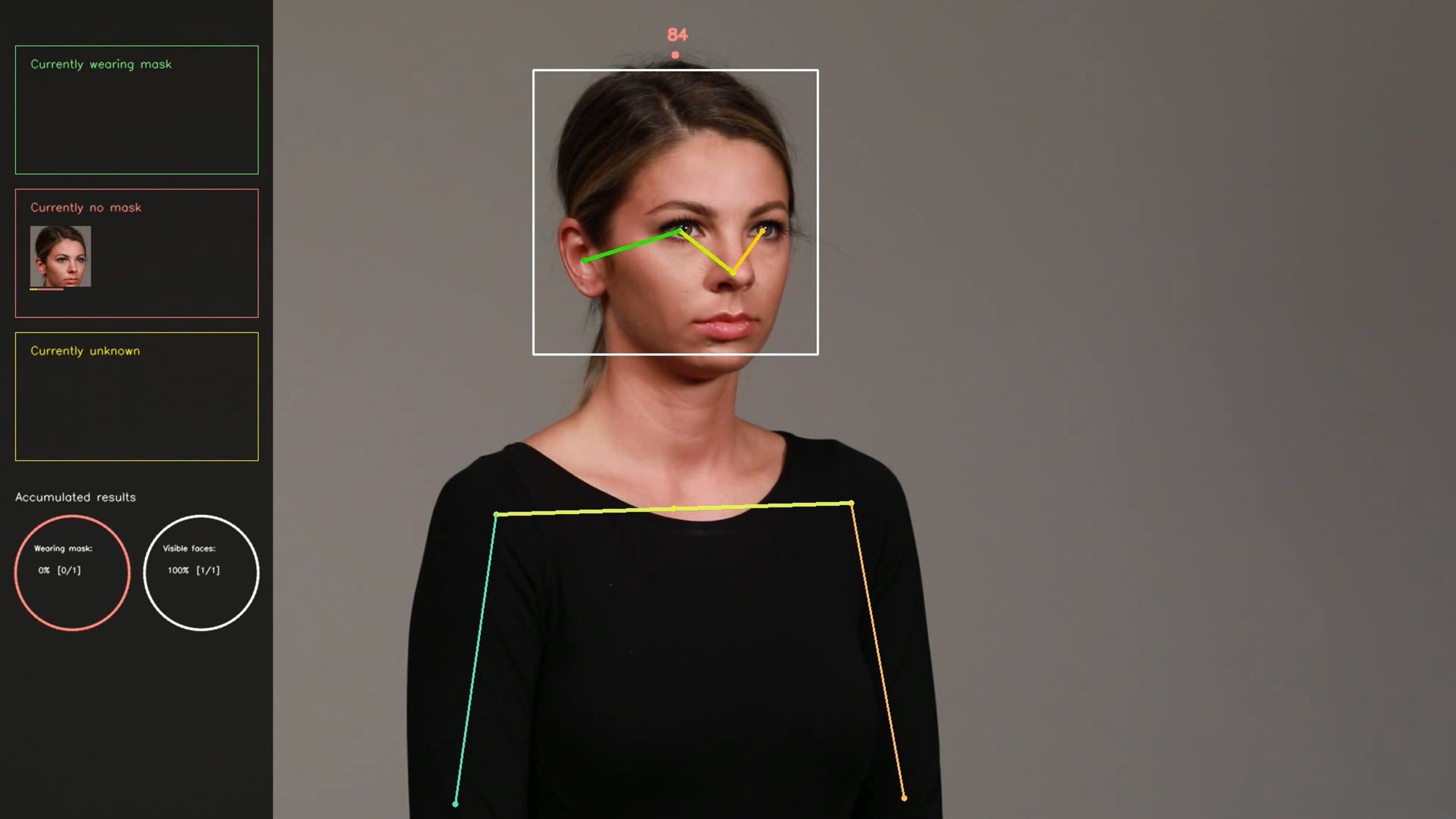

Developers say that mask recognition software in theory bypasses privacy issues because the programs don’t actually identify the people. Such software is trained on two sets of images: one to teach the algorithm how to recognize a face (“face detection”) and a second to figure out how to recognize a mask on a face (“mask recognition”). The machine learning algorithm doesn’t identify the faces in any way that can link a face to a specific person, because it doesn’t use a training set—the set of examples used to train such programs—with faces that are linked to identities.

Companies that have developed mask recognition software say that they ultimately want this technology to be used in broad ways that help people set policy or enhance awareness campaigns.

“If we can compute the number [of people who are complying with the mask mandates], people can make policies and monitor on whether or not they need to do another campaign to push mask usage,” says Alan Descoins, the chief technology officer of Tryolabs, a company based in Montevideo, Uruguay, that’s developed mask recognition software. “Or if people start getting bored about COVID, and start not wearing masks, then there might need to be more publicity to make people aware.”

LeewayHertz’s algorithm, for example, could be used in real time and integrated with closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras. From a given frame in a video, it isolates images and organizes them into two categories, people who are wearing masks and those who are not. Currently, this recognition software is being used in “stealth mode” in multiple settings in the United States and Europe. Restaurants and hotels are using it to make sure the staff is complying with wearing masks. One airport on the East Coast of the United States is also testing the technology on-site, says Taykar.

These private companies would have control over this data and how it’s deployed. Department stores could use it to dole out face coverings to noncompliant patrons, for instance, or a company could fire an employee who refuses to comply with wearing masks in the workplace.

While Taykar sees a strong reason to use mask recognition software in private spaces, public use might be more fraught: “If you’re in Times Square and there’s no social distancing, what do you do with that data? Would you want to put their photo on the billboards?”

The gaps in best intentions

James Lewis sees how mask recognition could be useful for maintaining compliance during the pandemic. But as director of the Technology Policy Program for the Center of Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., he is more concerned about the lack of rules that govern how this collected data gets used.

As it stands, the U.S. does not have a federal law that governs data privacy. Instead, the country relies on a patchwork of regulations relating to specific sectors, such as health, financial transactions, and marketing. In addition, corporations and entities that collect our private data don’t have to tell us what’s happening to it.

The situation has made many people distrustful. Three months before COVID-19 made it to the U.S., a Pew Research Center survey found that Americans generally feel “concerned, confused, and … [a] lack of control over their personal information.”

Critics of mask recognition also think that this new technology could be prone to some of the same pitfalls as facial recognition. Many of the training datasets used for facial recognition are dominated by light-skinned individuals. In 2019 Joy Buolamwini, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, and the AI Now Institute’s Deborah Raji investigated the accuracy of commercially available datasets used by major tech companies. When they checked the performance of recognition systems using an algorithm trained with the standard datasets, and then using a new set of faces with much more racial and ethnic balance, the researchers found that the algorithm was less than 70 percent accurate in identifying new faces.

One more aspect of machine learning to take into account: Nobody really knows what the algorithm is using to make its decision. Say, for instance, you want to train an algorithm to recognize a cow. “You think you’re showing the model a bunch of examples of a cow, but you don’t realize that in order to come up with the label of cow, [the algorithm] might be looking at the grassy fields in the background,” Raji says.

Applying that principle to facial or mask recognition: it’s possible that the machine learning models could pick up on other “background” features, such as race and gender, that would cause it to make mistakes about whether someone is wearing a mask. “There are other artifacts that influence [the algorithm’s] decision,” Raji says—and machine learning researchers are just coming to terms with this limitation of the technique.

She also believes that getting people to wear masks might not require a technological fix in the first place. To her, mask recognition feels like “technology theatre,” introducing software—and igniting privacy debates—to address a problem while completely side-stepping the underlying issue.

To get people to comply with mask usage rules, there’s a better way than using recognition systems that have the potential to infringe on civil liberties, says Aaron Peskin, a city supervisor for San Francisco who led a 2019 bill banning the use of facial recognition by law enforcement.

“Walking around with that level of invasion doesn’t make for a healthy society,” Peskin told National Geographic. He noted that police in New York City were stationed at Washington Square Park to hand out face masks to passersby.

Just this week, Portland, Oregon has passed a law that would ban public and private use of facial recognition, becoming the first city where using the technology is illegal. But Oregon also has a state-wide mask mandate, and Hector Dominguez, the Smart City Open Data Coordinator for Portland, sees mask recognition as different from facial recognition with regards to its privacy risks.

“We’re in the middle of a crisis. We need to start creating more awareness around privacy” with regards to how data gets used or shared in general, he says. Even though Portland’s facial recognition ban wouldn’t affect the use of mask recognition systems, Dominguez is wary that mask recognition systems would in fact capture more: “Masks are not going to stop facial recognition,” he says.

Ultimately, the pitfall of mask recognition is that it might set a dangerous precedent for what happens when the pandemic is over, say its critics.

“There’s a willingness to relax the rules when it comes to anything related to COVID,” says Lewis of CSIS. “The issue is, when this is over, will we go back?”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital