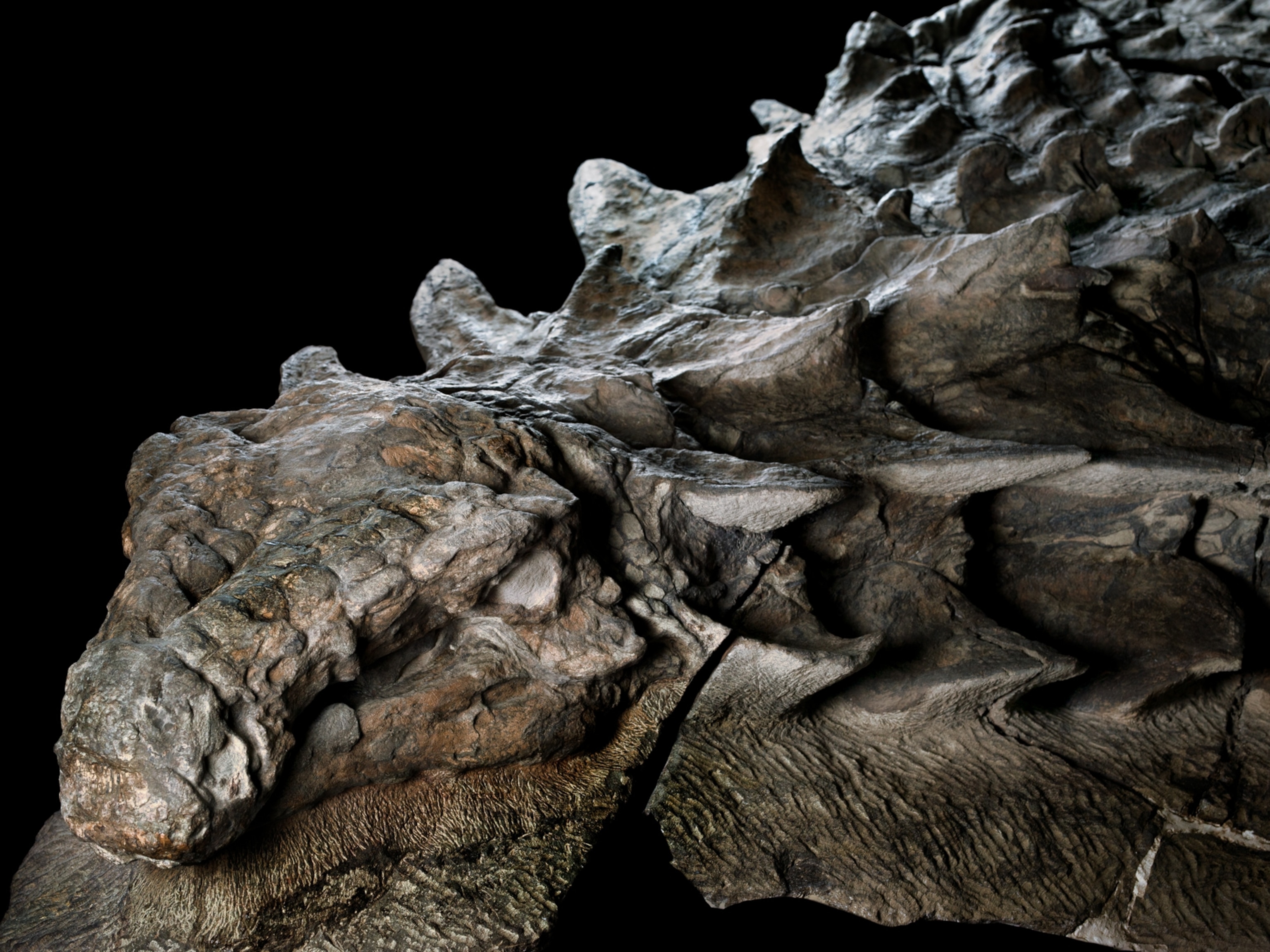

A spectacular new amber fossil from Myanmar holds the skull of the smallest prehistoric dinosaur ever found: a bird-like creature that lived 99 million years ago and grew no bigger than the smallest birds alive today.

The fossil, described today in the journal Nature, measures just 1.5 centimeters long from the back of the head to the tip of the snout, about the width of a thumbnail. The skull's proportions suggest that the animal was about the same size as a bee hummingbird, which would have made the newfound dinosaur lighter than a dime.

The tiny creature appears to be most closely related to the feathered dinosaurs Archaeopteryx and Jeholornis, distant cousins of modern birds. Researchers suspect that like those animals, the small dinosaur had feathery wings, but without more fossils, they can't determine how well it flew. And despite its hummingbird-like proportions, the tiny dinosaur was no nectar feeder. Its upper jaw bristled with 40 sharp teeth, and its huge eyes—suited for spotting prey in the foliage—have features unlike any seen in other dinosaurs. Fittingly, the creature’s genus name is Oculudentavis, derived from the Latin words for eye, tooth, and bird.

No creature alive today is built quite like Oculudentavis. “It’s revealing a completely different ecological niche that we never knew existed,” says study coauthor Jingmai O’Connor, a paleontologist at China’s Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology. “It’s fun, but it’s also a total puzzle, and everything about it is so weird.”

“This is truly one of the rarest and most spectacular of finds!” University of South Florida paleontologist Ryan Carney, who wasn’t involved with the study, says in an email. “Like capturing Cretaceous lightning in a bottle, this amber preserves an unprecedented snapshot of a miniature dinosaur skull with exciting new features.”

A snout of sharp teeth

When Lida Xing first saw the fossil, he thought it was “too strange.” The paleontologist at the Chinese University of Geosciences and lead author of the new study thought the animal’s long snout and large eyes suggested it was an early bird. But Xing was surprised that it had so many teeth, seemingly more than any other toothed bird from the Cretaceous. A full 23 teeth, each less than half a millimeter long, stud the creature’s upper right jaw alone.

To get a better look at the skull, Xing took the lump of amber to a high-powered x-ray facility in Shanghai to capture features as tiny as the width of a red blood cell. He then sent the scans to O’Connor, a specialist in bird-related dinosaurs, and what she saw gobsmacked her.

“This [fossil] was so pristine and so well-preserved,” O’Connor says. “This thing was super perfect.”

To suss out the dinosaur’s relative age, O’Connor and her colleagues pored over scans of the skull and looked at how much its bones had fused together, an indication of the animal’s maturity. The researchers determined that Oculudentavis died at or near adulthood—making its petite size all the more unusual.

Eyes like no other bird

The unusual creature also had eyes so large, they would have bulged out of the sides of its head. Puzzled, O’Connor decided to contact paleontology’s “eye guy,” Lars Schmitz, a researcher at California’s W.M. Keck Science Department who studies the evolution of vision.

When Schmitz first saw the skull scans, he realized that the eyes resembled smaller birds’ proportionately large eyes, which strengthened the case that the Oculudentavis fossil came from an adult.

Reptiles and birds have small bony rings in their eyes that help support the visual organs. The plates comprising these rings are usually shaped like narrow rectangles, but in Oculudentavis, the tiny bones are shaped like ice cream scoops. “The shape you see there, that isn’t really seen in any other bird, or any other dinosaur,” Schmitz says.

The only animals today with similarly scoop-shaped eye bones are diurnal lizards. As far as the researchers can tell, Oculudentavis used its unusually large eyes to forage during the day, snapping up insects with its toothed snout.

The most similar bird today might be the tody, a small-bodied Caribbean bird that preys on insects, says Jen Bright, a biologist and bird skull specialist at the University of Hull. But tody skulls are twice the size of the Oculudentavis fossil. “To find a vertebrate fossil this small is kind of mind-blowing,” she says. “It’s such a weirdo, I love it!”

O’Connor speculates that Oculudentavis’s strange features may have developed in its unique prehistoric environment. In ecosystems with limited resources such as islands, evolution can push animals to miniaturize, and the remains of a marine creature called an ammonite suggest the Burmese amber deposits formed on islands, or at least on coastlines.

“The tiniest vertebrates alive right now are these tiny little frogs from Madagascar, and they’re predatory, the same way we hypothesize that Oculudentavis was,” O’Connor says.

Digging up fossils—and controversy

Oculudentavis first came to light in 2016, when Burmese amber collector Khaung Ra acquired two specimens from a mine, including the tiny, mysterious skull. Ra donated the fossil to the Hupoge Amber Museum in Tengchong, China, which Ra’s son-in-law Guang Chen directs. The dinosaur’s species name, khaungraae, honors Ra’s donation.

The fossil is the latest discovery from the amber mines of northern Myanmar, whose caches of fossilized tree resin hold the remains of the tiniest denizens of an ancient rainforest. In recent years, paleontologists have found insects, a snake, and even some remains of feathered dinosaurs entombed within the amber. No scientist has done more to catalog these amber fossils than Xing, whose research is partially funded by the National Geographic Society.

As Burmese amber’s scientific value grows, so too do ethical concerns around its study. Many significant amber fossils start out in the hands of private collectors, raising questions about future scientists’ access to the specimens. Miners also face unsafe conditions, and the mines lie within Myanmar’s Kachin state, home to a long-simmering conflict between the Myanmar military and rebels fighting for Kachin independence. A 2018 military offensive to take over the mining areas displaced thousands of indigenous Kachin, according to the Kachin Development Networking Group.

According to Xing, the Hupoge Amber Museum is working to establish a museum in Myanmar, and Xing and other researchers are trying to ensure scientific access to amber specimens by returning them to the country once conflict in the region dies down. “It is the best thing to leave the important amber [fossils] in the country [where] they were found,” he says in an email.

As work continues to return Myanmar’s amber pieces, scientists will remain on the lookout for more bits of Oculudentavis. Already, Xing has heard rumors of a missed connection. The amber holding the Oculudentavis skull reportedly came from a bigger lump with preserved feathers, but by the time Xing saw the remains, the two pieces had been separated, cut, and polished, preventing him from confirming they came from the same source.

Schmitz, for one, is enchanted by the possibility. “Oh, I can’t even describe it!” he says. “The skull is so odd ... who knows what else we’ll learn in addition to what we’ve described so far?”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them? - This biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the AndesThis biologist and her rescue dog help protect bears in the Andes

- An octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret worldAn octopus invited this writer into her tank—and her secret world

- Peace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thoughtPeace-loving bonobos are more aggressive than we thought

Environment

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

- Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security, Video Story

- Paid Content

Food systems: supporting the triangle of food security - Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?Will we ever solve the mystery of the Mima mounds?

- Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?Are synthetic diamonds really better for the planet?

- This year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning signThis year's cherry blossom peak bloom was a warning sign

History & Culture

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

- How technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrollsHow technology is revealing secrets in these ancient scrolls

- Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.Pilgrimages aren’t just spiritual anymore. They’re a workout.

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?This ancient cure was just revived in a lab. Does it work?

- See how ancient Indigenous artists left their markSee how ancient Indigenous artists left their mark

Science

- Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of yearsJupiter’s volcanic moon Io has been erupting for billions of years

- This 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its timeThis 80-foot-long sea monster was the killer whale of its time

- Every 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost timeEvery 80 years, this star appears in the sky—and it’s almost time

- How do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tipsHow do you create your own ‘Blue Zone’? Here are 6 tips

- Why outdoor adventure is important for women as they ageWhy outdoor adventure is important for women as they age

Travel

- This town is the Alps' first European Capital of CultureThis town is the Alps' first European Capital of Culture

- This royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala LumpurThis royal city lies in the shadow of Kuala Lumpur

- This author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomadsThis author tells the story of crypto-trading Mongolian nomads

- Slow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capitalSlow-roasted meats and fluffy dumplings in the Czech capital